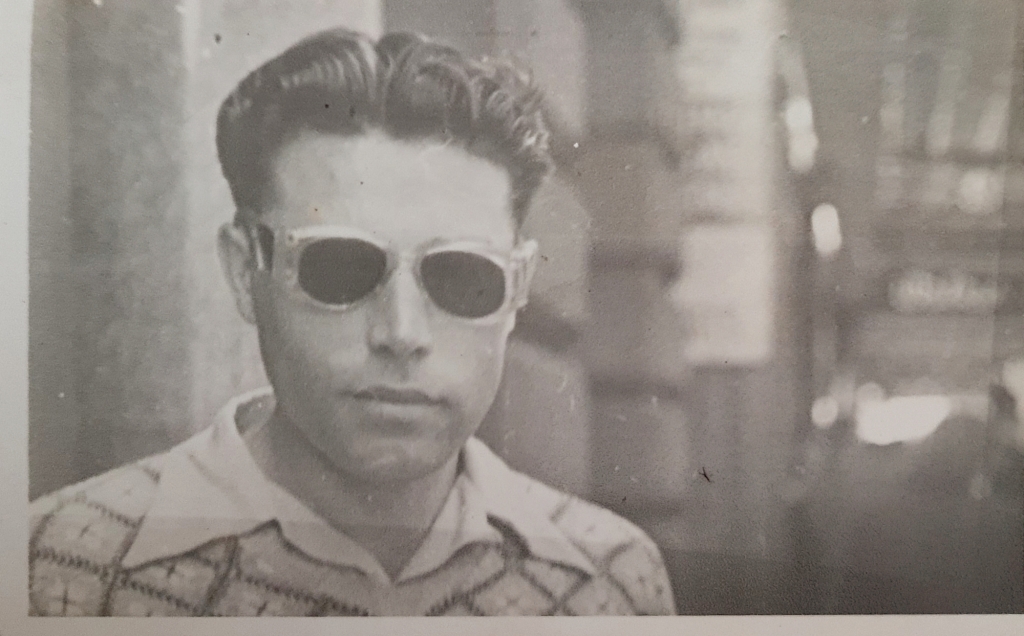

My father, Nanu, was born 99 years ago on this day.

In some ways he was a simple, uncomplicated sort of man. He loved peace, quiet and the company of people who connected him to his homeland in the Caucasus. He was proud, stubborn, could hold grudges over seemingly trivial things, yet was a doting grandfather and loyal family man. Reflecting on the sort of man he was gives me much insight into who I am. As I grow older I also reflect more on his pain and trauma, especially as a post war refugee – a man wrenched from people he loved and a nation that has all but evaporated in modern-day Russia.

The following are some reflections on his birthday, mostly taken from eulogies that my brother, Adam and I wrote for his funeral on 6 October 2006.

Growing up in the Caucasus

(photo courtesy of WorldAtlas)

Nanu was born in a small town called Abazahabla in the North Western region of the Caucasus. Unfortunately, a town of this name is unknown to Google. This was the same year that the republics of Karachay-Cherkess and Adyghe were created as autonomous provinces in the Soviet Union. Nanu’s origins were Cherkess and his native language was Abaza. Apparently only 35,000 native Abaza-speaking people are found in Russia today. The Cherkess belong to the ethnic group known as Circassian, who are one of many nationalities native to the Caucasus region, which sits between the Black Sea to the West and the Caspian sea to the East. The largest and best known of these people groups are the Georgians.

He was the oldest of six children born to Narik and Mulitkhan. He adored their memory. I can never remember him saying anything critical of them, although he was fond of talking about how his red-headed mother, Mulitkhan would often lose her temper with him and chase him around the kitchen. My images of my Dad are filtered through the stories he regularly told me from my earliest years. Even now I can imagine him as a naughty boy who would sometimes be led by silly impulses. His body bore the scars of war, yet the one on his chin came from a time he decided to kick a horse in the family barn. The response was a far more effective kick from the horse that left him unconscious. He would often tell this story as the only occasion that his father lost his temper with him. Perhaps the parental rebuke was more intimidating than the kick. As far as I am aware, he never kicked a horse again.

Nanu had two sisters, Fatima and Halakook and three brothers, Musa, Dzumaladin and Kamaladin. Both sisters died during my Dad’s exile years, as did his parents. He only ever said good things about his immediate family.

Nanu’s brother, Dzumaladin on the right and cousin Ali

Brothers reunite with Nanu (seated) in 1989

Nanu was very popular on his return

Nanu dancing his native “Lezginka” with friends and relatives on his return

I’ve often reflected on the patriarchal nature of my father’s culture, which was borne out in some of his attitudes and behaviours. (One story he told from his reunion in 1989, was when he sat at a table as the guest of honour for his first meal. After a few moments, he asked “where are the women?” He was politely rebuked, “Nanu, have you so easily forgotten your customs?” My Dad told me this story with a little wry smile.) Yet, the affection he had for his mother and sisters seemed almost poetic.

In fact, he had a poetic, even heroic perspective of his nation. His was a people of great beauty and dignity. The women were purported to being the most beautiful in the world and the mountains were the most stunning, or so he would say. His sense of etiquette and personal manners were also highly tuned and he could easily be offended if people did not reciprocate in like manner.

It is one of my sad reflections for him that after he returned from the four weeks to his homeland in 1989, that his heroic narrative subsided. He repeated many times after his return that Australia is the best country in the world. It felt like he had lost his innocence, even at the age of 67. I feel very sad for him, even as I reminisce.

Surviving World War 2

At the age of 19 Nanu was conscripted into the Soviet army. He began life as a member of the horse-drawn artillery, (clearly because of his ability to manage horses), fighting the German army during 1942-43 in their offensive on the Eastern Front. He was introduced to the rigours of army life by seeing a fellow soldier executed because he shot himself in the foot, trying to fake a battle wound. He himself was wounded on two occasions, both times in his feet. A third occasion he became severely ill from dysentery, after taking a cusp of water from the hoof-print of a horse to satisfy his thirst. Each time he recovered and was sent back to fight.

His last action as a soldier was, along with others, to blow up a bridge to slow down the advancing German artillery. Unfortunately he and a few other soldiers were separated from their unit and he didn’t hear the command to retreat. He was captured by German Scouts and rounded up with at least a dozen other Soviet soldiers. After waiting for almost a day, he noticed different German soldiers – ones who were wearing black uniforms. One of these, an officer, commanded that they be lined up in an open piece of ground and he questioned each of the men briefly, asking their names and ranks. Without notice a command was given and the black uniformed soldiers opened fire on each of the men.

Nanu woke up sometime later, thinking he was in heaven. But he could hear a voice – a Ukrainian soldier asking if anyone was alive. He also heard another sound. It was the gargling of a dead soldier who had been shot in the neck. When he came to himself, he realized that he was still alive – without a scratch, along with his Ukrainian colleague. They were the only two survivors. But he was covered in blood. Miraculously, the Germans were nowhere to be found and they made their way to the nearest village.

One woman took pity on him, and brought him to her home giving him clean clothes from her husband, who was also fighting in the Soviet army. She passed him off to the occupying Germans as her younger brother. No-one bothered him. After some days he decided to return home – a journey, which Adam and I reckoned to be approximately 300 kilometres. He wasn’t sure how long it had taken him to walk home, but he did it. It was summer, and he slept in haystacks and fed himself from the orchards that he passed by.

His return home was probably the most moving story of his war experience. The last time Dad shared this story he could barely finish it. His father was no longer home. (He had been sent by the Germans into Italy, where he was to die before the end of the war.) When Dad finally arrived home, he went to the kitchen. His mother’s back was to him. He called to her “Uma”. Without turning around she said “What do you want – I already fed you,” thinking it was Musa. He replied, “What, don’t you want your son?” She turned around shocked to see Nanu. I can’t describe to you the joy and the sorrow that he had in sharing this story – and I heard it many times. It was one of the most precious moments in his life.

He wasn’t home long, when the Germans sent him to a labour camp in Germany. It was the last time he was to see his mother and his sisters. It would be another 46 years before he saw his brothers and other family members in the Caucasus again.

Ultimately, Nanu was a survivor. There were many more life-threatening episodes and seemingly miraculous events before he eventually boarded a ship to Australia.

Home in Australia

Nanu was accepted by one of the humanitarian programs to come to Australia. Amazingly, he did this with false identity papers provided by Jewish friends. I love this fact as he was a Muslim, although he was never particularly devout. He was also a Soviet soldier who had been captured by the enemy. Stalin’s policies were brutal for all Soviet prisoners of war. Creating a false identity was a matter of survival.

His earliest years were spent in South Australia, working in the bush on a public works program. He eventually made his way to Sydney, where he met the woman who would become my mum.

Perhaps because of the trauma of wartime and the need for stability, Nanu worked in only two jobs for his remaining working life. The first was as a marble polisher in a small factory in Annandale and the second for Australia Post as a Mail Sorter. Dad had an amazing memory and was able to rattle off any town and corresponding postcode in Australia. In fact, he was a repository of all sorts of general knowledge.

He also had an amazing gift for languages being fluent in his native Abaza, Russian, German, English and a workman’s knowledge of Italian and French, as well as many of the languages around his native region. His grasp of English also manifested itself in creative ways to convey displeasure or move one to action such as, “are you made of glass?”, which was his way of saying don’t stand in front of the television, or “remove yourself”, which meant “get out of my chair”. My Dad was nothing, if not direct!

There are still many more stories for me to unpack, largely for myself as I consider the man he was and the life he lived.

The value of a single life

What is the value of a person’s legacy?

How do you measure the value of a single human life?

For me, I believe in a God who is both Creator and Sustainer. I also believe in the reality of human choice and the profound influence we all have on those closest to us. This is seen in no more impactful way than in the influence parents have on their children. My Dad had a profound influence on me, shaping the way I see the world in millions of ways that I am probably not even conscious of. Ultimately, I am thankful for his life – the good, the bad and the ugly.

I am also thankful for the unseen hand that somehow drew together a seemingly infinite plethora of circumstances, which resulted in the influence of that single life on mine.

This is wonderful! I had a little cry ❤️❤️❤️

LikeLike

Thanks Gabriel – a marvellous and moving recollection/reflection. Best wishes. Murray

LikeLike

Thanks Gabe! What a fascinating story of survival and resilience. Thank you for telling it. You honour his memory and his spirit by doing so as well as enriching the lives of all those who read it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

WHAT A WONDERFUL EULOGY GABI.HAPPY BIRTHDAY UNCLE NANU. YOUR NEICE ANNA.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for telling this incredible story of survival and resilience Gabe. You have honoured your father’s life and spirit in doing so and expanded the perspective of anyone lucky enough to read it. The photos really bring his story to life. I enjoyed them so much, especially the one of him dancing on home soil. God bless him and may he rest in peace after packing in several life times worth of experiences into but one. You have much to be proud of.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful story Gabe. People of that generation had great resilience, and somehow managed to carve a meaningful life out of such tragedy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your fathers story blew my mind, as do so many of the stories that you hear from people from this time period. People back then were just so strong and brave! You told the story wonderfully Gabe.

LikeLiked by 1 person